Muskegon Chronicle January 20, 1974

Daring Surfers Take

Wintry Lake Michigan Ride

By ELEANOR ANDREE

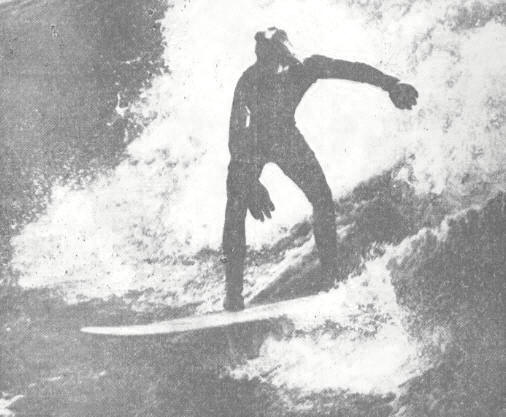

COLD RIDE . . . When the water is 34 degrees, surfers need gloves and more than a little expertise to ride the waves of Lake Michigan. Howard Benninck takes a fast ride on the winter surf at Grand Haven. Only the formation of shelf ice halts the surfing.

GRAND HAVEN — Winter visitors to Michigan — if they are observant —will find it hard to believe what they see — surfers on fragile boards, riding the white water of lake Michigan until the ice closes in.

They do not much resemble their bronzed, bikini-clad summer selves, but surfers they are — some of the best. Clad in wet suit, helmet and gloves, they find the best challenges in Lake Michigan surfing comes not in summer, but when winter flings its icy gauntlet and whips the cold, gray winter into long, strong swells that challenge them to their best efforts. And their best is very good. It has to be, for lake Michigan in winter is no place for a beginner.

To find out what kind of surfer would accept so cold and dangerous a challenge, we talked to Jerry Kaman, a surfer who never gets into any of the pictures because he take them all.

Surfing goes year around on Lake Michigan, but the best, most consistent surf occurs in the winter and early spring. Spring and summer surf, when it does occur, generally comes up after a storm, so the best summer surfing is done by keeping an eye on the sky. By late October, however, the west and southwesterly winds of summer give way to the prevailing north-westerly winds of fall and winter, and the good surfing begins. Hence, a really dedicated surfer, unlike most tourists, goes to Florida in the summer and returns late in the fall in time for the winter surf.

The question naturally arose as to how one could earn a living and devote so much time to following the surf. Jerry Kaman, for one, is now working three jobs.

“I came back form Hawaii last winter,” he said “and got a new car. I shouldn’t have, because now I have that to worry about. But I’m catching up the payments, and I’m going to Florida in early spring. There’s another group going to Puerto Rico for about three months in summer. Everyone works about a half year, and then takes three or four months off.

“Bob Pushaw — he’s 22 — went to Mexico for three months. My brother Jack, who’s 24, is saving to go to South Africa now. He lived in Hawaii for half a year, and came back and then went to Baja last summer. He’s been surfing since 1964 when it all started.”

What does it cost to live for surfing?

“A lot!” was the rueful reply. “You just make it! You can’t go out and buy a lot of extravagant things. You either surf or you have things. It’s just a matter of what’s important to you.”

There even used to be a Great Lakes Surfing Association, we learned, which folded because of financial problems.

In 1968 came what Kaman calls a “surfing revolution.” Before that time, surfboards were 9½ to 10 feet long. The new concept of the short board came from Australia, and the length quickly went to 9 feet. By 1969, boards were 7 feet long, and by 1970-71 they were down to 5½ to 6 feet. Also during this time, there came what Kaman calls “a trend from India which took hold, and everybody became ‘his own person’ more or less.”

Will there be surfing clubs again? It depends, he believes, on the young surfers coming up. The older surfers, (“older” meaning those in their 20s) are on their own, working and traveling — following the surf.

“The high school kids,” he said, kind of keep together, so they might start something. There was a beginning in Muskegon, on the shore of Lake Michigan, this summer.”

Surfing clubs start as most associations do, by the coming together of people with similar interests. The Great Lake Surfing Association was started in 1964 when Bob Allen, Craig Van Single and Rick Sapinski were in high school. They got there friends interested, the membership grew little by little, and then competition started between the high schools in Grand Haven, Muskegon and Grand Rapids.

“The kids all went to different schools,” said Kaman, “but they all surfed together.” The common bond formed the association.

There are no organized events scheduled for the rest of the winter. Only real surfers, what Kaman calls the devoted ones, those who are really making a life out of it, will be on the water the rest of the winter. But they are surprisingly many.

A real challenge, and no place for a beginner, is the Rock Pile at Grand Haven’s south shore.

“You have to start halfway out the pier,” Kaman explained. “There are big rocks on shore, and if you wipe out there, that’s where you get your fractures and broken bones. But people are really nice. If your board winds up there, they will ease it out of the rocks and pick it up till you can swim in and get it.”

In California or Hawaii, he said, you have to paddle out a mile to a mile and a half to catch a wave.

“That seems long,” he said, “but there is no strong current or undertow to fight. On Lake Michigan, if you paddle right out against the surf, you just don’t make it.

“At the Sand Castle on the north shore, you go out a half to three quarters of a mile and at the Rock Pile you go out half the length of the pier. On a southwest swell, when the waves down shore are breaking about two or three feet, the waves at the Rock Pile are three to six feet. That’s because the waves hit the side of the pier, double in size and fold over. It’s no place for a beginner. The surf out of the southwest carries you right into the pier. An inexperienced surfer will slam right into it. You must make a hard bottom turn and swing right. Also, you can’t paddle out on the water in the usual way. You must walk out on the pier and jump to the lower level, and from there into the water.

“The trick there, is standing in the center of the pier waiting for the swell to calm down just enough so you can jump down to the lower level so you can throw your board on the next swell. You just launch yourself off the pier, and know how to judge waves. One that looks huge may be small when it arrives. The small one behind it may pick up in size and be big,” Kaman said.

How do you know? You learn the hard way. Waves generally travel in sets of three to five waves. The first looks large, but dwindles off. Usually the third and forth are the largest of the set. Kaman doesn’t know why, but when you see a set of waves, he says, you just know that the first, second and fifth won’t be that large. The third and fourth will.

To most of us, November means bare trees, cold wind and blue-gray skies. To Jerry Kaman and his soul brothers, November is the beginning of real surfing.

“In November,” he explained, “you get northwest winds all the time. When you get a big surf on the north side of the pier, you’ll get waves that line up on the south side of the pier from a quarter to a half mile down the beach, and roll like Northern California. Then you get beautiful rides. They’re not choppy at all, Long rides just like the ocean. That’s the good thing about winter and northwest winds — the long rides you get on the south side of the pier.” In December last year, however, his timing was off a little, and the wave picked him and his board up, dragged then down the side of the pier and sucked him into the lake.

“That really wrecked my board,” he mourned. We refrained from asking what it did to him.

Enthusiasm aside, what about the cold? Can your body really take the winter wind and the frigid water? Yes, he said, the wind is entirely bearable in a full wet suit.

“There are a lot of nice ladies on the pier who ask, ‘Aren’t you cold?’, or ‘Aren’t you freezing to death?’ But it’s a thing of nature. You build up resistance. You have to. After I came back from Hawaii and tried it, I almost froze. I was completely out of shape for it.” Winter surfers make a point of going out each Christmas Day or January 1st. They continue to surf until the ice gets too heavy, and begin again early as possible in the spring. If the ice breaks up early, it may be late May. But it’s not an obscure, dying sport.

“Lots of new guys come out each winter,” Kaman said. Groups from around Michigan City, Ind., and Muskegon travel up the lake and try Grand Haven, and we do the same down there. A lot of tourists come out to watch in winter, too, but if they’ve never done it, they don’t try, because we go out when the surf is five to eight feet, and that’s no time to be a beginner. They surf a lot in summer though.”

It is no longer possible to rent boards at Grand Haven, we learned, but Felix’s Marina, about three miles inland, is open all year around, and is able to provide equipment and services.

When the cold begins to take its toll, when the leg muscles give out and age begins to tell on the man who lives to surf, what then? Kaman had some answers:

“Mike Hanson, who used to surf here,” he said, “has a surf shop in San Diego, and he’s making a heck of a lot of money and he’s still surfing, and that’s all he has been doing.

Robert August has dropped out of public view, but he’s designing surfboards for a California company. He’s making good money to, and still surfing all the time.

“A lot of professional surfers have gone into skiing. Mike Doyle, world surfing champion, for instance, designed a new ski — one with two foot holds for mountain skiing. Surfers are doing lots of things in related sports.

“Then there’s snow surfing. You rip out the rudder on your surf board and go downhill. You can have a riot — a real great time. Or you can make a snow board of wood. Shape it about three feet long and seven inches wide. It’s kind of hard to stand on, but a lot of fun.”

Not having been aware of winter surfers before, we were surprised to learn that Michigan has great numbers of them, as Kaman told us. “Anywhere from Michigan City to the Upper Peninsula. Hardly anyone notices, but they’re there. When the surf is up, just look. You’ll see ’em out there!”

If you’d like more information on winter surfing, write Terry Laug at 151 Emmett, Grand Haven. He took care of all the association’s correspondence years ago, and still gets a lot of letters. Or you can write or stop in at the West Michigan Tourist Association at 136 Fulton Street, Grand Rapids.

If you need a new interest to spark the dull days of winter, it’s hard to think of a more stimulating challenge. You might — if you think your mind and body can stand the gaff — try riding the wild offbeat of the Lake Michigan winter surf, and become a member of a rare brotherhood. One thing is certain — you’d never become stodgy or bored!